|

Monthly archives: March 2004

AL East Preview

2004-03-29 13:25

Yankees, Red Sox Oh, Muse! What causes lying at the root Blue Jays, Orioles, Devil Rays and seeps in, slowly, whose quiet weakness

Permalink |

No comments.

AL Central Preview

2004-03-28 21:52

Tigers Twins Royals Indians White Sox

Permalink |

No comments.

Joseph Campbell's 100th Birthday

2004-03-26 12:07

Joseph Campbell was born 100 years ago today, so it's an appropriate day to express my gratitude to him. Campbell is for me what Bill James is to baseball statisticians: the guy who opened my eyes to a completely new way of thinking. Back in college, I was struggling to understand why I was so obsessed with baseball. Campbell's insights into relationship between myth, culture and human psychology provided me the answers I was looking for. Baseball is my personal mythology. Now, I don't buy Campbell's story about myth hook, line, and sinker. As a guy whose personality type is that of an architect of systems, I can see that Campbell's explanations don't quite work as an architecture. DNA is the building block of life, and from that, springs forth a subconscious mind that spews a common form of myth? It doesn't quite fit. There's a missing step between DNA and myth. That's partly what my Keeping Score in the Arts series was about: how a simple brain architecture can produce the complex set of behaviors we see in human culture. Nonetheless, Campbell's insights are invaluable to me. Campbell's mantra of "Follow your bliss" also helped me feel less guilty about my obsession. All my baseball activities: watching on TV, going to the ballpark, reading, blogging, writing silly poetry, playing fantasy games: that's my bliss. No apologies. So where do I go from here? Will Carroll recently asked a similar question, wondering about blogging as a career. He said we need to ask ourselves, "What's in it for me?" Short answer: youneverknow. If you follow your bliss, one thing will lead to another. But what that other thing will be is a mystery. As Campbell put it: If you do follow your bliss you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while, waiting for you, and the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living. When you can see that, you begin to meet people who are in your field of bliss, and they open doors to you. I say, follow your bliss and don't be afraid, and doors will open where you didn't know they were going to be. So I'll follow my bliss, and go dancing through doorways, just to see what I will find. Happy Birthday, Joseph Campbell, and thanks for the advice.

Permalink |

No comments.

Immediate Prophecy

2004-03-25 18:20

Am I a jinx or something? Just hours after I had written that the A's bench is not a bottomless pit, my statement gets tested. Mark Ellis is out 6-8 weeks after dislocating his shoulder in a collision with Bobby Crosby. We'll soon find out how valuable Ellis' defense really is. If Hudson and Mulder start giving up a lot more hits than usual this April, we'll know why. Although Frank Menechino is also hurt, the A's shouldn't miss much offensively. And this illustrates what I enjoy most about watching Billy Beane work. You can talk all you want about Hudson, Mulder, Zito and Chavez, but Beane's real genius shows up in the 35th-40th men on the roster. He creates depth at every position. When Ellis gets hurt, he not only has one competent backup, he has three (with Baseball Prospectus projections):

The entire division has only one middle infield backup, Eric Young, who is a better hitter than the A's fourth-string second baseman. That's why Billy Beane is so good. And that's why I said the A's can win a war of attrition. I just wish I wasn't so right so soon.

Permalink |

No comments.

AL West Preview

2004-03-25 12:04

Angels Athletics Mariners Rangers

Permalink |

No comments.

Trigonomystery

2004-03-25 00:39

Dan Werr has posted some very cool maps over on Baseball Primer. Check them out. My favorite map is the one which divides the US into areas based on which MLB ballpark is closest. For those of you who enjoy puzzles, here's one for you, based on that map: My house is very close to the dividing line between two teams. That made me curious which ballpark I was actually closer to. So I pulled up some maps and a ruler and measured. As the crow flies, it looks like it's about 5.2 miles to the nearest ballpark (7.7 miles by car). The second nearest ballpark is 5.6 miles away (but 13.5 miles by car). So I live about 350 yards from the dividing line. Which ballpark do I live closest to? Also, I can walk about 350 yards from my house and see one of the ballparks. Which one?

Permalink |

No comments.

Rosebudstein

2004-03-24 08:44

John Dowd, the Pete Rose investigator, recently theorized that George Steinbrenner pressed Bud Selig for Rose's reinstatement because it would help Steinbrenner's own Hall of Fame chances. Denials everywhere.

Permalink |

No comments.

Server Problems

2004-03-24 00:15

I'm cursing my dumb ISP.

Silly me for assuming that buying a "static IP" meant my IP address would be static. My ISP had given me a week's warning, but I rarely check the email address they sent the warning to, so I didn't see it until it was too late. It took me over six hours to notice the problem and then fix everything that needed fixing. I apologize for any inconvenience. You may now return to your regularly scheduled humbug.

Permalink |

No comments.

NL East Preview

2004-03-23 00:03

Phillies Marlins Expos Braves Mets

Permalink |

No comments.

Thoughts from a Bored Bullpen

2004-03-22 00:20

Ever think about the space-time continuum?

Beane may not be perfectly cast as Eve, but we'll give him the part because he is so hairy.

When she died I had a dream. She came to me and said, "The space-time continuum moves in mysterious ways. When the great leader of your land is caught lying and unwillingly removed from power, you shall receive my gift." So I've watched with keen interest while Nixon, Reagan, Clinton, and Dubya have all been accused of lying. Alas, impeachment never succeeds. But If I win this pool, everything becomes clear. Grandma Agnes was actually referring to Martha Stewart.

My oldest daughter is osmosing baseball. Much to my delight, she chose a baseball theme for her 7th birthday party this weekend. It's fascinating to watch her interest in baseball grow. She's not really into the competition or the players much; her interest seems to be mostly cultural: the styles, the music, the history. I wonder if it's just her, or if this is the Women-Are-From-Venus path into the sport. My wife did her best Martha Stewart imitation for the birthday party. She transformed the backyard into a baseball stadium. Every kid had their number retired on the wall:  One of the party games we played was pickle. The kids got to run the bases and the adults tried to tag them. It brought back forgotten memories of hours upon hours spent playing pickle as a kid. With the modern aversion to stolen bases, and the hyperorganized nature of youth activities these days, I wonder: do kids play pickle anymore?

Why? It makes no sense! Does somebody up there hate us? They didn't say that. Read the book. Joe Morgan moves in mysterious ways. Hilarity ensues.

Permalink |

No comments.

Critics Considered Harmless

2004-03-19 00:06

Brian Micklethwait on his Culture Blog said, "Critics who explain why TV shows are so good are the most dangerous kind, because they stop you ever enjoying it again." My baseball audience can imagine the question this way: Critics who explain why baseball teams are so good are the most dangerous kind, because they stop you ever enjoying baseball again.In either case, I think this is wrong. Judging from the hostile reaction to Moneyball, it's a common fear: that if you explain the mechanics of an art form, the enjoyment you get from it will cease. But this fear is based on a faulty understanding about how the brain stores knowledge.

I have proposed that our judgments of any kind of art, whether it's a TV show or a baseball game, come only from the subconscious system. Decisions arising from the subconscious system are instant and automatic. Our conscious decisions are slow, rational and deliberate. But we don't need to deliberate very hard to decide whether we like a TV show or not. It just happens. Our judgments about art match the characteristics of the subconscious system better. As you observe a TV show, or a baseball game, your subconscious system notices all kinds of patterns. The patterns you've seen many times, you learn to ignore. Those are clichés. If you see something unusual, though, you need to create a new memory for this new pattern. We like it when that happens. On the other hand, when a critic explains a pattern to you, a different kind of memory is created. The critic is not giving you an actual pattern, but a fact about a pattern. An actual pattern would be a nondeclarative memory, stored in your subconscious. But the fact is a declarative memory. It's conscious. My hypothesis claims that you don't use your conscious memories when you make your judgments, only your subconscious ones. If I'm right, knowing a fact about the artwork should not have any bearing on whether you like an artwork or not. I know an awful lot of people who understand the facts about baseball inside and out. They know all the statistical probabilities for any given situation. But knowing these facts does not reduce their enjoyment of the game. That's because the facts reside in a brain subsystem separate from the source of their enjoyment. Facts are facts and patterns are patterns and never the twain shall meet.

Permalink |

No comments.

The Nomads of Kamchatka

2004-03-18 12:00

Suppose you're an indigenous reindeer herder on the frozen tundras of Kamchatka. You live in yurtas, like this one:  Every few days, as the reindeer graze the land barren, you pack up your home and move to another place, and rebuild your camp. You're never settled, always changing. This has been your life for as long as you can remember.

What would you do? Perhaps you'd be happy about the easier lifestyle. More likely, though, you'd be in total shock.

A's fans are nomadic. We settle down for a while with some players, let them graze awhile, and then move on to something else. Reggie, Catfish, Rickey, Canseco, McGwire, Giambi, Tejada...our players always leave. The team itself has moved twice, and is always threatening to move again. We're used to it. We know we're just a whistle stop on a journey to some other place, and everyone else is just passing through. So now I'm sitting here, trying to think about Eric Chavez sticking around for six or seven more years, and well, I can't do it. It's beyond my ken, completely incomprehensible. But give me some time. I think that maybe, eventually, I could get used to this.

Permalink |

No comments.

Defending Aaron Gleeman

2004-03-17 14:56

Some people take baseball far too seriously, and criticize anything and everything. It reminds me of Teddy Roosevelt's quote: It is not the critic who counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly, who errs and comes short again and again; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement; and who at the worst, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat. So when a Baseball Primer thread turned critical of young blogger Aaron Gleeman, I felt the need to respond: To those who say a baseball blogger's heft You go, Aaron.

Permalink |

No comments.

NL Central Preview

2004-03-17 00:21

Astros Cubs Cardinals Reds Brewers Pirates

Permalink |

No comments.

NL West Preview

2004-03-16 00:02

Padres Giants Dodgers Diamondbacks Rockies

Permalink |

No comments.

Elsewhere on the web...

2004-03-15 09:07

Will Carroll's question about why we blog ("What's in it for me?"), sent me into deep thought over the weekend. Then, I happened to come across a whole list of old SNL Deep Thoughts on Eve Tushnet's site. I think the answer to Will's question is this one: Perhaps, if I am very lucky, the feeble efforts of my lifetime will someday be noticed, and maybe, in some small way, they will be acknowledged as the greatest works of genius ever created by Man. I couldn't have said it better myself. And I encourage you to come back to my site, because Tushnet also posts: Before a mad scientist goes mad, there's probably a time when he's only partially mad. And this is the time when he's going to throw his best parties.

That's why I encourage you to go check out Mariner Musings, where Peter White has a whole series of haiku about Mariner players.

Permalink |

No comments.

Spring Training Scrapbook

2004-03-12 16:46

I took a quick trip down to spring training last weekend. I used some poetic license, and assembled a Spring Training Scrapbook of my trip. Atop my photos, I pasted some screen-captured clippings from other baseball blogs. If you're been reading a lot of baseball blogs lately, you might recognize some of the text I used. Requires Flash, 244kb.

Permalink |

No comments.

Lake Placid Memories

2004-03-11 00:25

OGIC points out a good story in the New Yorker about Igor Larionov going to see Miracle, the film about the 1980 US hockey team. Larionov was just a youngster then, and he just missed out on making that Soviet team. His memories were not quite as happy as the film's. My memories of the 1980 Olympics were a bit different, as well. In 1979, my parents divorced and I moved with my mother to Sweden, after spending my first thirteen years in California. It was my first real winter, and I guess my young body wasn't prepared for it. Just days before the 1980 Winter Olympics started, I caught pneumonia. If you're going to be bedridden for two weeks in the middle of winter in Sweden, you couldn't pick a better time than during the Olympics. Sweden only had two TV channels back then, both government-run. They usually only broadcast from about 6pm-11pm, and most of their programming was horrendously boring stuff like pottery making and polka music. But during the Olympics, they broadcast nearly every event live and in its entirety. I watched it all. The TV commentators were rooting for all the Swedes, and I got caught up rooting for them, too, especially after Thomas Wassberg won the 15km cross-country gold medal. He passed the finish line just 0.01 second ahead of a Finn, Juha Mieto. I had never imagined cross-country skiing could be exciting, but that was an amazing race to watch. The commentators went absolutely nuts. They showed the finish over and over again for days. In the smallest fraction of a second, Wassberg became a hero for life in his homeland. Swedes have a small-town attitude towards their country, a refreshing humility about their little place in the big world. They don't really expect to win. They don't expect anyone else to pay any attention to them. Victories of any sort are always a surprise. Losses are not scandals, just the expected outcome for such a small group of people. But there is one big exception to this: ice hockey. When the Swedes and Americans tied in the first hockey game of the tournament, the commentators were extremely disappointed, even upset. The Swedes were expected to win, and the tie with this lesser team would hurt their chances at a medal. Although the outcome suited my background, I empathized with the Swedes' disappointment. Little did anyone suspect that this would be the only game USA wouldn't win.

Now, I've seen Michael Jordan. I've seen Barry Bonds. I've seen Wayne Gretzky. But to this day, Ingemar Stenmark is the most dominant athlete I've ever seen. Most Americans would probably guess that Björn Borg is Sweden's biggest sports hero. After all, he won Wimbledon five times in a row. Stenmark and Borg were both born in 1956, so I was lucky enough to live in Sweden during both their peaks. Borg was big, of course, but Stenmark was bigger. Stenmark completely dominated slalom and giant slalom skiing. In his career, he ended up winning 86 World Cup races. Alberto Tomba is second, and he trails Stenmark by a whopping 36 wins. But the number of victories only tells part of the story. Stenmark was so good, he didn't really even try during his first run. Basically, all he did was make sure he didn't fall down. In the second run, he would go all out. If he finished in the top 10 after the first run, you could be pretty sure he would either win the race or fall down trying. I remember one time he decided to go all out for both runs of a giant slalom race. He won by almost four seconds. Whenever Stenmark skied, the entire country of Sweden would stop. I remember being out the town market one day during a World Cup race, and one of the vendors had a TV. When Stenmark's turn came, everybody in on the square stopped what they were doing, and huddled around this one TV set to watch his run. Because Stenmark was so dominant, I think Swedes felt more worried about a fall than excited about him winning Olympic gold. So when Stenmark ended up winning gold in both slalom and giant slalom (coming from behind each time, of course), they didn't really explode with joy and surprise like they did about Wassberg. The prevailing emotions were pride and relief.

When I got to the practice, my teammates were talking about the Sweden-Finland match. I was tying my shoes. Then someone asked about the USA-USSR game. One teammate said, "USA won." I looked up, surprised. "No way," said another teammate. "They did." "You're joking, right?" "No, USA won, 4-3." Nobody could believe it. Then they all turned and looked at me, the American. I looked back with a "hey, I'm cool" smile, and resumed tying my shoes.

But that wasn't going to happen. USA was a team of destiny. Sweden had the unfortunate fate of being the next team the Soviets played after the Miracle on Ice game. The Soviets absolutely clobbered Sweden, 9-2, to take the silver. Sweden settled for the bronze. From the Swedish point of view, the results were acceptable, but not great. When I hear stories about Al Michaels call, part of me wishes I had been in America to be immersed in the pure joy and surprise of gold, instead of the mild satisfaction of bronze. But then I would have missed a similar joy and surprise when Wassberg won, and would not have experienced the total dominance of Ingemar Stenmark. I guess I'll just have to follow Larionov's lead, and go see the movie.

Permalink |

No comments.

In Other Words...

2004-03-10 18:20

Art is the language

Permalink |

No comments.

Keeping Score in the Arts #6: A Better Mousetrap

2004-03-10 16:30

This is the sixth in a series of six articles.

The creation of art is a feedback loop between Android Brain and Animal Brain. Android Brain works through the steps of creating a work of art. The steps involve speaking in the language that Animal Brain understands: novelty, patterns, emotions, satisfactions and alarms. Animal Brain gives the artist feedback about the quality of the artwork, about whether new nondeclarative memories are being formed by it. Based on that feedback, the artist, in Android Brain mode, then alters the work. Many artists just trust their own Animal Brain feedback and follow that. For those who are successful doing that, good for them. Don't change a thing. But I think many artists would probably see the quality of their work improve if they had some good guidelines for Android Brain to follow. Good rules can help artists be more aware of the choices they have and tradeoffs they make. Android Brain is built for step-by-step instructions. It's methodical. There are already many good instruction books for artists to follow, but I think we can use the language of memory formation to make our explanations more precise. Such explanations would not only be useful for pure artists, but also for advertisers and producers of goods whose measures of success are not counting new memories, but counting sales. As Virginia Postrel points out in her book The Substance of Style, aesthetic quality is becoming an important part of our economy. A similar feedback loop pertains to art critics, too. Animal Brain is the source of our reactions. Android Brain has facts and rules about how art should work. It's the source of our explanations. A good critic will move back and forth between Animal Brain and Android Brain, testing what their rules tell them against what their actual reactions are. If their reactions differ from their rules, they'll adjust their rules. The goal of art criticism is to explain to Android Brain what's going on in Animal Brain. Some bad critics favor one system or the other. A bad Animal Brain critic will have a reaction and try to explain it without using any logic at all: I opine, therefore I'm right. That's not helping Android Brain, which wants logic. A bad Android Brain critic will have rules about what art "should" be, and analyze according to those rules. But if you're not testing the rules for accuracy against Animal Brain, you're likely to have ineffective rules.

I can imagine people reacting negatively to thinking of art as a form of engineering. Even to me, it feels like the magic of it might be diminished. But because of that inaccessible data inside of our Animal Brain, I think art will always retain a certain mystery. The conversation between Animal Brain and Android Brain need never end. To work with things is not hubris

Permalink |

No comments.

Keeping Score in the Arts #5: A Lifetime of Art

2004-03-10 07:15

This is the fifth in a series of six articles. In my last article, I used my hypothesis to explain some commonly seen phenomena about art. In this article, I want to explore how our tastes change over the course of our lifetimes. Babies When my daughter was three months old, she laughed for the first time. I bent over, so that my daughter could only see my hair. Then I suddenly lifted my head up, so my daughter could see my face again. My daughter burst out into a fit of giggling laughter. The scientific term for this behavioral phenomenon is "peekaboo". Peekaboo is an art form. If you reveal your head too slowly--no laughs. If you lift your head up and down too quickly--no laughs. To achieve maximum laughs, must hide your face, and then reveal it, with a certain optimal delay. My three-month-old daughter, who could not talk, who could not eat solid food, whose only major accomplishment of human behavior was to hold her own head up without it flopping over, was suddenly demonstrating a sense of aesthetic quality. Child psychologists say that peekaboo tests the concept of "object permanence". Object permanence is the concept that an object still exists even though you cannot see it. Before object permanence, when the face is gone, it's gone. When it's there, it's there. Object permanence turns peekaboo into a paradox: the face is not there (I can't see it), but it is there (objects continue to exist even while not visible). It's not there, but it is there! Two separate, and indeed contradictory, memories get associated with each other, and the result is a new memory. Peekaboo's effectiveness lasts for several months. At first, it seems you can play it endlessly and get a laugh every time. Slowly, though, the game gets more sophisticated. Your timing needs to be more precise to elicit laughter. You can't emerge from the same place each time: you have to suddenly emerge from unexpected directions to get a laugh. Eventually, sometime after the child's first birthday, peekaboo stops working altogether. Peekaboo becomes a cliché. The child has become completely habituated to the idea of object permanence.

Preschool age Why do kids like cartoons? Do you know of any young child who prefers a live action film to an animated one? I don't. As you saw with object permanence, one new memory can become half the building block for another. It's a long process, though. Children take much longer to become habituated to new things than adults. Ask any parent who's had to tell the same story over and over and over. And over. And over. And over. Adults are habituated to so many more things than young children are. Children experience much more unrecognition with any given artwork than an adult does, and far less cliché. Cartoons are simpler in every way than live action film. With live action, there is so much else going on: the colors, the lighting, the backgrounds, the body movements, the facial expressions--they are all more complex than a cartoon. There is so much more the brain needs to filter, and so the young brain becomes much less likely to recognize patterns in live action film. In cartoons, however, there is much less information to sort through. The child can more easily recognize the patterns, the plots, the characters and their emotions--and trigger all those pairs of neurons, and create new memories.

School Age When my daughter turned five, she was given a (fake) coonskin cap from a relative who had visited the Alamo. She loved it. When she started kindergarten, she wore it on her first day of school. She's in first grade now, and she still sometimes wears it to school. That won't last. Nobody else in her school wears a coonskin cap. Somewhere between second and fourth grades, ages 8-10, what other people think about art suddenly becomes hugely important to us. The clothes that looked fine before suddenly are rejected because that's not what everyone else is wearing. Kids will suddenly develop passions for sports or pop music, because that's what their peers are doing. In other words, art becomes a social act. Before this, a child's reaction to a work of art is almost purely its own. After this point, what other people do enters the database of patterns we build up in our brain, and becomes a factor in our judgments. The child is building more and more sophisticated patterns every day. More and more adult-level patterns move from unrecognition into recognition, as the child-level patterns move into cliché. Young adults Mature adults often hate popular artworks aimed at a teenage audience. Adults see them as cliché, but the teenagers don't. As the teenagers mature into young adults, and experience those patterns over and over again, that begins to shift. Why don't college radio stations play bubble-gum pop music? Because college-age students are finally at the age where they can easily recognize the clichés of popular culture. At an age where young adults are establishing their own independence, there's a natural rebellion against the standards of popular culture from the previous generation. The passing of generations is probably a vital creative force. In the effort to reject the old generation, a new generation puts a lot of effort into finding new kinds of patterns that they can identify as their own.

Mature Adult So why don't we just hate everything by the time we're say, 50 years old? By then, we've probably seen so many patterns we become nearly impossible to please. This is where I think my focus on habituation breaks down a bit. I focus on it because I think it plays such a huge role in how we perceive art. But all the other forms of conditioning can also affect how we form nondeclarative memories in our Animal Brain. Nostalgia is the result of a kind of associative conditioning, similar to Pavlov's dog. When you first enjoy a work of art, you get a positive emotion associated with it as a sort of byproduct. Those positive emotions will remain with that artwork, and any similar artworks that remind you of it. You become conditioned to enjoy that kind of art, the way the dog became conditioned to expect food after hearing a bell. I still listen to a lot of the same music I listened to in college. Yes, I can recognize the clichés in the old stuff, but I still like it anyway. A lot of the new stuff is either too clichéd or unrecognizable to me. I'm just an old fuddyduddy now, I guess. Next: A better mousetrap.

Permalink |

No comments.

Keeping Score in the Arts #4: Some Explaining to Do

2004-03-10 00:15

This is the fourth in a series of six articles.

Permalink |

No comments.

Keeping Score in the Arts #3: Hypothesis

2004-03-10

This is the third in a series of six articles.

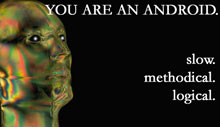

One system is intuitive, fast, and subconscious. It's designed to recognize patterns and react automatically to them. It holds your memory of motor skills and habits. We're calling that system our Animal Brain. The other is rational, slow, conscious. It's designed to follow step-by-step instructions. It holds your memories of facts and events. We're calling that system our Android Brain. Animal Brain tends to dominate our behavior. It broadcasts all kinds of information to Android Brain. But Android Brain has no easy way to communicate back to Animal Brain.

Now we're ready for my guess as to how art works. Remember that this is just an attempt at reverse engineering: to make something that behaves the same way the original does. The internal workings of the brain may be quite different from this. If so, that's OK. I'm really only concerned that the outputs are similar. I propose that art is simply a way to communicate with our Animal Brain. We do that by taking advantage of Animal Brain's own nature. Animal Brain is constantly on the lookout for unusual patterns in its environment, so that is what we give it with art. So here's my hypothesis, using my terminology: The purpose of art is to provide a way for Android Brain to communicate with Animal Brain. Now for the same thing, using scientific jargon: The purpose of art is to enable the declarative memory system to communicate to the nondeclarative memory system. Or, to give System 2 a way to talk to System 1. If my hypothesis is correct, all we need to measure the quality of art is some kind of nondeclarometer, which can count the appropriate chemical signals from the Animal Brain's nondeclarative memories as they are created. New memories send out strong chemical signals. Habituated memories release weaker chemical signals. These chemical signals tell Animal Brain what to pay attention to and what to ignore. I'm hypothesizing that the strength of these chemical signals are what we are measuring when we judge the quality of a work of art. Drat! I just Googled "nondeclarometer" and got zero hits. Neural scanners are still pretty crude, but I imagine someday it might be possible to measure memory creation fairly accurately. But for now, measuring art is possible only in theory, not in practice.

The brain is a complex organic machine. I'm sure this simple hypothesis is just that, too simple. But if our goal is usefulness rather than accuracy, simple is probably better, anyway. A hypothesis is a beginning, not an ending. We can test our hypothesis against observable phenomena, and adjust it as we learn more. So let's go use the hypothesis to explain some common phenomena we observe about art.

Permalink |

No comments.

Keeping Score in the Arts #2: A Brain Lesson

2004-03-09 09:30

This (somewhat long) article is the second in a series of six articles.

In his book The Metaphysical Club, Louis Menand describes an observation Oliver Wendell Holmes made about our legal system. Even though our legal system is set up to make decisions like this:

(Holmes then went on to make some quite illogical decisions based on his own practical experience, including ruling that professional baseball should be exempt from anti-trust laws.)

Daniel Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize for Economics. His studies have focused on how people make economic choices. Kahneman and others have found that people have two decision-making systems. One system is intuitive, the other is rational. From an interview in Strategy+Business (registration required, emphasis mine):

Kahneman tried to train people to make decisions using their rational system in instead of their intuitive system. But the effort was fairly futile: Our research doesn't say that decision makers can't be rational or won't be rational. It says that even people who are explicitly trained to bring System 2 thinking to problems don't do so, even when they know they should.In other words, he found the same thing Holmes did: that people have an extremely strong tendency to judge first, then reason later.

A just machine to make big decisions  Humans appear designed for inefficiency. Judges make decisions before they consider the evidence. Businessmen ignore logic and opt for less-than-optimal economic choices. Perhaps the song I quoted above is correct. We'd be better off having some kind of android making our decisions for us. The perplexing thing is that each of us already has an android-like system for making decisions within us: Kahneman's System 2. Let's call this system Android Brain. Android Brain does things methodically, in sequence, and follows rules to arrive at logical conclusions. You can give Android Brain step-by-step instructions, and it will follow those instructions. It's programmable. It's available to use. So why do we ignore it? Why do we so strongly prefer the intuitive system that is more error-prone? Are we designed wrong? Not really. There's a very good reason we do this.

Quick, tell me exactly what you do with your left big toe when you walk. Don't know? Well, actually, you do know. If you didn't know, you couldn't walk. So how come you can't tell me? Well, just as there are two reasoning systems in the brain, there are two memory systems, too. Scientists call the two types of memory declarative and nondeclarative. Declarative memory is what we usually think of when we think of memory. It is our conscious memory. It contains facts and events. When it fails, such as in Alzheimer's Disease, we lose our ability to remember what happened in our lives. Declarative memory is strongly associated with Android Brain, our reasoning system. Its processing center is an area of the brain called the hippocampus. Sometimes called procedural memory, our nondeclarative memory is often overlooked because these memories are not conscious. They hold things like motor skills and habitual behavior. The reason you can't tell me what your left toe does when you walk is because this is a nondeclarative memory. Your conscious mind does not have any access to this data. The processing center for nondeclarative memory is an area of the brain called the amygdala (a-MIG-da-la). The amygdala has a second purpose besides handling your nondeclarative memories. It's also the central processing center for your emotions. When you're afraid, angry, excited, or happy, that's your amygdala talking. The fact that the amygdala handles both your motor skills and your emotions is significant.

Imagine you're a zebra, grazing on the savannahs of Africa. There's a light breeze blowing the tall grass around. Suddenly, you notice a strange indentation in the grass. You feel fear, and in fear, you jump up and run away. A good thing you did, too, because that indentation was a lion sneaking up on you. This is Kahneman's System 1 in action. Let's call this system Animal Brain.

Animal Brain did three things to save your life:

This is why we have a strong preference for the decisions of Animal Brain over Android Brain. Any ancestor who favored using the slower, rational decision system of a Android Brain was more likely to be eaten by lions. The ones who preferred the quick decisions of Animal Brain stayed alive to pass their genes on to you.

So how did our imagined zebra know the difference between the motion of the grass caused by the wind, and that caused by the lion? Let's take a slight detour and look at memory. The process for creating Android Brain's declarative memories is pretty complex. Animal Brain's nondeclarative memories are more primitive and easy to explain. In 1949, a scientist named Donald O. Hebb proposed a theory about how learning works in the brain. All learning, whatever the senses involved, uses the same basic mechanism: pairs of neurons firing together. Fifty years later, a 1999 study out of Princeton University led by neurobiologist Joe Tsien revealed the genetic mechanism for Hebb's rule. The gene, called NR2B, creates a protein which acts like a double lock on a door: It needs two keys -- or two signals -- before it opens. As such, it is an excellent tool for creating memory, a process that fundamentally consists of associating two events. If two signals arrive at the same time -- maybe one results from seeing a lit match and the other results from a sensation of pain -- then the receptor is triggered and a memory is formed. Animal Brain memories are altered by various forms of conditioning: repeated exposure to stimuli in the environment. The most famous example of conditioning is Pavlov's dog. The dog drooled when he heard a bell, because he had been conditioned to expect food after a bell rang.

One form of conditioning is called habituation. In the book Memory: From Mind to Molecules, authors Larry Squire and Eric Kandel describe it like this: ...habituation is learning to recognize, and ignore as familiar, unimportant stimuli that are monotonously repetitive. Thus city dwellers may scarcely notice the noise of traffic at home but may be awakened by the chirping of crickets in the country.When we're first exposed to something new, a new memory is formed. If we are repeatedly exposed to it, though, and it proves harmless, we get conditioned to ignore it. Thus, a zebra who is repeatedly exposed to the pattern of grass waving in the wind will become conditioned to ignore it. However, a change to that pattern could indeed have alarming consequences: it could be a lion. The zebra won't ignore that stimulus.

Now, back to the two brain systems. Let's compare them:

The reasoning skills of our Android Brain seems rather unique to humans, although other mammals do have declarative memories. It should be obvious that all mammals, if not all animals, have a brain system that works more or less like Animal Brain. Although the human Animal Brain shares many things in common with a zebra's, they are not identical. Humans have evolved some very important differences. At the Neuroesthetics conference I went to, Dan Fessler, an anthropology professor from UCLA, gave a presentation about shame and pride, two uniquely human emotions. These emotions depend on the ability to imagine what someone else is thinking. For example, you don't feel ashamed if you're alone and you discover your fly is open. You only feel ashamed if you know that someone else knows that your fly is open. But by far the most important difference between a human's Animal Brain and a zebra's is language. Language is a function of our Animal Brain: it is an automatic and subconscious skill. We speak and understand without deliberate effort. It has a sophisticated type of pattern recognition (listening), and an associated motor skill (speaking).

What happens when the two systems need to interoperate? It was pointed out in the Neuroesthetics conference that the conversation is extremely one-sided. Animal Brain broadcasts all kind of information to Android Brain: emotions, sensations, decisions, language. But Animal Brain seems to be completely unaware that Android Brain even exists. Hardly any information at all flows in the other direction. Remember, Animal Brain is designed to keep you alive and reproducing. From an evolutionary standpoint, nothing is more important than that. And Animal Brain knows it.

In this delightful children's book, Frog and Toad have a problem. Their Animal Brains are telling them to eat more cookies. Their Android Brains are telling them not to. They are finding it extremely difficult to ignore their Animal Brains. Animal Brain is like that guy you meet at a party that you can't get away from. He talks and talks and never listens to a word you say. If you try to ignore him, he STARTS TALKING LOUDER. If you try to turn away, he pulls you back: THIS IS IMPORTANT! DON'T MISS A WORD! You have no choice but to humor him. Animal Brain: what a jerk. Now, if his message is "there's a lion sneaking up on you," you're grateful for his message. But if you're on a diet, and he keeps telling you "EAT ANOTHER COOKIE", it would be better to ignore his message. But it's very hard to do so. He's so insistent! Animal Brain assumes everything is urgent. Every situation is life or death. How do you handle a jerk like that? Well, one way is to use your own strengths. One of Android Brain's strengths is the ability to follow rules. So we come up with rules that help us manage the behavior of Animal Brain and correct its errors: Ten Commandments, Twelve-Step Programs, Seven Effective Habits, that sort of thing. Another way is to exploit his weaknesses. And Animal Brain does have weaknesses. That's where art comes in.

Permalink |

No comments.

Keeping Score in the Arts #1: A New Science

2004-03-09

This is the first in a series of six articles.

Aesthetics is the branch of philosophy that deals with the nature and value of art. Theories of aesthetics have been around since Plato and Aristotle. None have delivered a useful way to measure art. But a new science is emerging, that gives us some hope of a solution. It's called neuroesthetics, the study of the relationship between the brain and art. I wanted to get a sense of the current state of neuroesthetics, so in January, I attended the Third International Conference on Neuroesthetics, which focused on "Emotions in Art and the Brain." A wide variety of speakers gave their thoughts on how the brain works in relation to art: neurologists, psychologists, evolutionary biologists, art historians and some artists themselves. The Washington Post wrote a good summary of the conference (registration required). I learned a lot, but I did not learn the one thing I most want to know: how do you measure the quality of a work of art? The speakers all either implicitly or explicitly avoided the issue. Neuroesthetics seems to be in a cataloging mode right now: gathering as many facts as possible. This makes sense. If neuroscience is in its infancy, neuroesthetics is a newborn sibling. Neuroesthetics has a long way to go before it can give mature, scientifically valid answers to any of its questions. That doesn't help me much. I'm just an amateur artist, but I want tools right now to help me build better things. By the time the science can provide me with something useful, I may be in a nursing home. A scene pops into my head: Guesses can be useful even if they aren't always accurate. Long before I had found out about neuroesthetics, I felt compelled to make a calculated guesses about how art worked. I did this by using my training as a computer engineer to approach measuring art as a reverse engineering problem. I knew what the inputs were (works of art), what the outputs were (judgments). The goal has been to design a new machine that takes the inputs and produces outputs similar to the original, and hope that it leads to useful information about art. I gathered the data I had, and began tinkering around with numerous possibilities for arranging that data. But it wasn't until I started learning more about the brain that I was able to find an algorithm that satisfied me. The resulting hypothesis proposes that measuring art is possible, but it requires technology that isn't currently available. Although we'll fall short of one goal--being able to keep score in the arts--we will meet another: finding useful tools for creating and analyzing art. Whether I'm programming a computer, writing a limerick, or just watching a TV show, I now find I can approach my artistic endeavors with more purpose and precision than I ever could before.

Permalink |

No comments.

Keeping Score in the Arts: Preview

2004-03-08 09:00

Suppose, for a moment, that there were no statistics in baseball. None, not even the score itself. No runs, hits, or errors were tracked. What would the sport be like? To begin with, everyone would have a different opinion about who won each game. You'd pick a winner based on how the experience of the game felt to you. Which team's play did you like better? "The long home run in the sixth inning was impressive. The home team was the winner, in my opinion."Nothing would have any set value. Perhaps you find the arc of a fly ball to be beautiful, and the team that seemed to hit the best fly balls is the one you'd pick as the winner. Who could argue against you? You like what you like, right? Pity, then, the poor statisticians, who would have no numbers from the game to analyze. They'd have to resort to measuring the opinions of the audience. How would you rate Sammy Sosa's performance today on a scale of 1 (bad) to 5 (great)?Intellectuals, of course, would come forward to take on the challenge of deciding who is best. We cannot trust mere public opinion with such a task. It takes experts to truly understand this stuff! So then we'd be flooded with essays like "Baseball Analytics: A Postmodern Approach", "The Influence of Global Capitalist Hegemony on Individual Player Evaluation", "Oedipal Dynamics in Team Construction", and "The Role of the Female Orgasm in Baseball Management Decisions". In other words, there would be an awful lot of humbug. I have felt for a long time that the arts would make a lot more sense if it had a statistic like "runs scored". If we knew exactly what we were trying to accomplish with a work of art, we could speak about it with more accuracy and less humbug. It seems like an impossible goal, but there's no harm in trying to reach it. So this week, I will present a series of articles where I explore the nature of art, why it's so hard to explain, and take a guess at how it could be measured. Next: A New Science

Permalink |

No comments.

a man had never been to Yankee Stadium

2004-03-05 09:54

a man had never been to Yankee Stadium one morning he grabs his bat he stops at nothing fence...smash a trail of destruction that will not stop

Permalink |

No comments.

Loneyness

2004-03-04 23:07

It's the first baseball broadcast of the spring. The veterans play a few innings, then step aside to let the youngsters have a turn. "James Loney is just 19 years old," says the TV announcer. "19 years old!" says my daughter, looking up from her dolls. She had been ignoring the game until now. My daughter is 3. She is impressed by 19. It still sounds like a kid's age to her, but it's older. Older means being-allowed-to-do-things. Older also means bigger, and bigger means being-able-to-do-things. James Loney is able to do things. "Wow, 19 years old!" she repeats. Back when I was 19, I-- Loney swings. His follow-through reminds me of David Justice. Justice and I are the same age. Justice retired from playing over a year ago. Sigh. Sometimes, older means not-being-able-to-do-things. Later, my daughter maneuvers into her booster seat for supper. As she's settling in, she sings from the D-O-D-G-E-R-S Song: "Leo Durocher, Leo Durocher, She has no idea who or what a Leo Durocher is, other than something that wiggles and twitches. Heck, I don't really know, either. He was before my time, too. But her little song makes me smile. Baseball is back, and the generations have resumed their conversations with each other. Suddenly, the world seems like a whole lot less lonely place to live.

Permalink |

No comments.

What I wot

2004-03-03 16:53

"To wot" meant "to know", but there was once a distinction between the two. Why wot left our tongue, the gods themselves, wotting no more than I, are ignorant. Swedish has two related words, "veta" and "kunna", which retain the distinction. "Veta" means "to know that", while "kunna" means "to know how". If you're describing a fact, you use "veta". If you're describing a skill, you use "kunna". Knowing that Josh Beckett is a pitcher and knowing how to pitch are two different kinds of knowledge. I have spent hours working on an essay trying to describe a particular distinction in the brain. This morning I realized the distinction is perfectly summarized by the difference between "veta" and "kunna". In English, it's a struggle to differentiate these two types of knowledge. A Swede will get it right away. I know the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which claims that people are limited in their thinking by the features of their native language, is out of fashion. But from my experience, some ideas just more naturally come to mind in one language than another. Just for fun, here are some other Swedish language features which lack a direct English counterpart:

Well, I tycker that this entry is lagom long. It's getting jobbigt to write more. I'm kissenödig. Dörrarna stängs.

Permalink |

No comments.

Witch Hunt

2004-03-02 12:29

Names! We've got names! And then? We'll be positively sure Blissful-- occur

Permalink |

No comments.

|

Score Bard's blog: now verse than ever!

About the Toaster

Baseball Toaster was unplugged on February 4, 2009. Frozen Toast

Search

Archives

2009 02 2008 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 2007 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 2006 10 09 08 07 06 03 02 01 2005 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 2004 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 2003 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 2002 12 10 09 08 07 05 04 03 02 01 1995 05 04 02 Greatest Hits

Email

toaster 'at" humbug.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||